As I write on February 3rd, OfCom has just launched a consultation around release of a block of 6GHz spectrum for wireless comms. It seems a good moment to talk about Wi-Fi 6E.

Before we start, let’s be clear what we’re talking about. Most of us are comfortable discussing the zoo of 802.11 standards, and this blog will largely be about 802.11ax. But the Wi-Fi Alliance, presumably aiming to assist the domestic consumer, has introduced a revised nomenclature that groups Wi-Fi technology into generations:

| Wi-Fi 1* | 802.11b (1999) |

| Wi-Fi 2* | 802.11a (1999) |

| Wi-Fi 3* | 802.11g (2003) |

| Wi-Fi 4 | 802.11n (2009) |

| Wi-Fi 5 | 802.11ac (2014) |

| Wi-Fi 6 | 802.11ax (2019) |

* Legacy tech isn’t being actively rebranded.

Unfortunately, this cleaned up schema is already causing some confusion. As we’ll discuss below, the true benefits of 802.11ax can only be realised in uncongested spectrum, but Wi-Fi 6 co-exists in the 2.4GHz and 5GHz spectrum with legacy devices and non-WiFi applications, so a new category has had to be introduced, Wi-Fi 6E, which is the version of 802.11ax implemented on hardware that can broadcast in the newly released and therefore pristine 6GHz spectrum.

Space to grow

In 20 years, Wi-Fi has done an amazing job. It manages to carry more data than any other access technology, utilising only a tiny 600MHz total slice of the available spectrum. But Cisco forecasts that by 2022, Wi-Fi will carry 51% of global IP traffic over some 549 million hotspots worldwide (Cisco’s annual Mobile Visual Networking Index (VNI)), and more spectrum must be made available to accommodate this continuing growth.

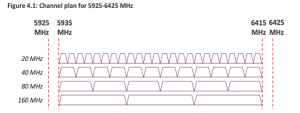

It’s not just traffic volume that drives the case for releasing spectrum. To realise the benefits of the most recent generations of Wi-Fi technology, wider channel bands must be allocated. However, the congestion caused by unrelated technologies and legacy standards occupying the same unlicensed spectrum is a problem. Add in dynamic frequency selection (DFS) technology intervening to protect licensed infrastructure applications like air traffic control radar and the result is that even if your Wi-Fi 6 hardware is technically capable of operating on a 160MHz channel in the 5GHz ISM band, it will very rarely find sufficient free, contiguous space to actually do so. This effect hobbles your hardware, and in many cases an upgrade from Wi-Fi 5 to Wi-Fi 6 will show little if any benefit at the single device level. Wi-Fi 6 does do a lot better at handling larger groups of devices, so there is still a net benefit, but it is only when the new protocol capabilities are deployed in ‘empty’ spectrum capable of allocating them high bandwidth channels that anything approaching the theoretical maximums of performance that make Wi-Fi 6 a game changer kick in. This is where Wi-Fi 6E, designed to run in a 6GHz channel reserved for it, delivers.

Fortunately, Ofcom has just announced consultation around proposals to release 500MHz of the 6GHz band exclusively for Wi-Fi 6E use in the UK; this corresponds with the lower end of the block being proposed in the US and matches that under consideration by the EU. These frequencies will be released for low power use to protect existing license holders.

Source: Ofcom

What’s so different?

The feature set of Wi-Fi 6E is likely to be identical to Wi-Fi 6, but those features will work to their full potential when given the bandwidth to breathe. The key features that will drive a better connectivity experience for your users are:

- WPA3 (wireless protected access v3): WPA3 is more resistant to brute force attacks than previous iterations. Wi-Fi 6 is the first generation to make WPA3 mandatory.

- MU-MIMO (multi-user, multiple input, multiple output): The current generation Wi-Fi 5 struggles a little with anything more than 4 connected devices. It can handle 4 at once, but any additional ones have to wait in a queue to pass traffic. Wi-Fi 6 can handle 8 simultaneous flows, so there’s less queuing and lower latency.

- OFDMA (orthogonal frequency division multiple access): this may be the really disruptive technology. Unlike previous generations of Wi-Fi which leave a channel open to a single device while its transmission completes, locking other devices out until they get a turn, OFDMA divides each channel into smaller sub-channels called resource units, so up to 30 devices can share a channel simultaneously instead of taking turns.

- TWT (Target Wake Time): By scheduling with the router when any given device will attempt to communicate with it, they can power down antennae in between these periods, conserving power and reducing latency. This also makes Wi-Fi 6 great for Internet of Things (IoT) applications, where the power budget is limited.

- No DFS: your devices are free to use the channels without external constraints designed to minimise interference with local licensed services.

What about 5G?

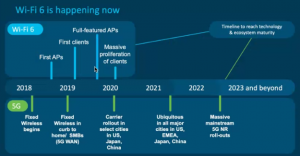

5G has received the vast majority of the hype but Wi-Fi 6/6E is going to make a similar impact. We are seeing research hinting that Wi-Fi 6 may be just as disruptive and likely to be quicker to market than a fully usable and pervasive 5G option. One thing is sure, that the marketing hype and early city-centre deployments of 5G will create expectations from the student population that we might have to look to Wi-Fi 6, and 6E in particular, to fulfill in the medium term.

What does all this mean for education?

We are all probably responding to similar drivers on campus: higher bandwidth demands from applications, more mobile devices per user, and higher user densities. Wi-Fi 6E addresses each of these areas to some degree, so seems a strategic next step in upcoming wireless refresh exercises.

A particular strength is likely to be improving performance in high density usage areas like lecture theatres and other teaching venues. This is already a particular challenge for wireless engineers, often overcome by stacking multiple access points on different channels in the same space. The combination of wider channel bandwidth, MU-MIMO and OFDMA should improve issues around simultaneous user number limits in a single space, or the dreaded “everyone trying to log into the same system at the same point in a lecture” problem that often brings networks crashing to a halt.

So, if you have a wireless refresh in your immediate future, give serious consideration to the 6GHz version of Wi-Fi 6 / 802.11ax – and keep a wary lookout for pre-certification chipsets that may still be on the market.

Useful reading:

- https://www.testandmeasurementtips.com/what-you-should-know-about-wi-fi-6-and-the-6-ghz-band/

- https://www.zdnet.com/article/what-is-wi-fi-6-and-why-youre-going-to-want-it/

- https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/21/18232026/wi-fi-6-speed-explained-router-wifi-how-does-work

- https://www.nctatechnicalpapers.com/Paper/2019/2019-the-promise-of-wifi-in-the-6-ghz-band

- https://www.zdnet.com/article/wi-fi-6-devices-capable-of-using-6ghz-band-to-get-wi-fi-6e-branding/

- https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0038/189848/consultation-spectrum-access-wifi.pdf